Some photographs are relics. Others are riddles.

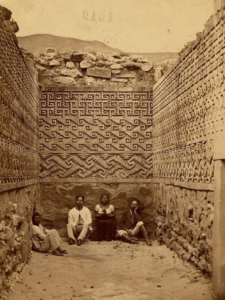

This one, taken over a century ago, is both. Sepia-toned, dust-laden, yet defiant against time’s erosion, it captures four figures sitting solemnly inside a narrow, stone-lined chamber. Their expressions are unreadable—not from lack of clarity, but from the sheer weight of the past pressing inward from every patterned brick around them. The walls are not blank; they are speaking. They hum with patterns—geometric glyphs and zigzag labyrinths—like a language carved in silence. This is not just a room. It is a sentence in the long, unfinished poem of the Zapotec.

The site is Mitla, an archaeological gem nestled in the highlands of Oaxaca, Mexico. And though it now stands open to tourists and scholars, at the time this photo was taken, it was still wrapped in the hush of mystery. It was, to the outside world, a puzzle box waiting to be unlocked.

The four people seated in the chamber aren’t just figures for scale—they are echoes of the human pursuit to understand origins. The two men in European attire likely represent 19th-century archaeologists or explorers, hardened by travel, eyes sunken by obsession. Between them sits a local woman, possibly a guide or member of the community, and beside her, a young boy leans against the stone in quiet resignation. Together they form a constellation of time: the curious outsiders, the rooted insider, and the child—symbol of both future and forgotten lineage.

But it is the walls that steal the breath.

Mitla, unlike the towering pyramids of nearby Monte Albán, wasn’t built to scrape the sky. It was built for silence, for reverence. The name Mitla derives from the Nahuatl Mictlán, meaning “Place of the Dead.” To the Zapotecs, this was Lyobaa—”Place of Rest.” And yet nothing about the stonework suggests rest. The mosaic panels that decorate the chamber’s interior are vibrating with sacred geometry. There is no mortar; the stones were carved to interlock with impossible precision, creating friezes that resemble mazes, lightning, rivers, and serpent scales. They do not simply decorate—they encode.

It’s believed these intricate patterns represented cosmological ideas: the duality of life and death, movement and stillness, chaos and order. Each zigzag might symbolize water or wind, both elemental forces in Zapotec cosmology. Others whisper of the underworld, of the soul’s passage through confusion and darkness toward rebirth.

Imagine the sound in this chamber. Or rather, the lack of it. The dry breath of wind funneling through the narrow opening above. The crunch of feet on sand. And perhaps, just perhaps, the distant echo of ritual chants once held within these walls—echoes so old that they only exist now in the grain of the stone.

The photograph invites us to time-travel.

Picture the builders of this chamber, hundreds of years before Europeans ever laid eyes on the valley. Hands calloused, minds precise, they lifted each stone not only with effort but with purpose. These walls were meant to be read by the initiated—high priests, shamans, perhaps royalty. They were the keepers of memory, passing down truths not in words, but in angles and repetition.

And now, centuries later, four strangers sit inside that sacred text, each unaware of what exactly surrounds them. They are in a book they cannot read.

Yet, there’s something quietly revolutionary about the photograph. It is not just documentation—it is trespass. These men entered a tomb not meant for them, sat within a geometry not designed for foreign minds. But instead of destroying it, they preserved it in their own way. And in doing so, they unintentionally passed the legacy forward, allowing new generations to wonder, to decipher, to respect.

There is an ache in this image too.

Because we know what comes after. Colonization. Suppression. The slow, grinding erosion of indigenous knowledge systems. The Zapotecs still exist, but the language of these stones—literal and figurative—has been partially lost. Their wisdom was not erased with violence, but diluted with time, indifference, and concrete cities that rose where spirits once walked.

And yet, somehow, Mitla endures.

Unlike so many ancient structures that succumb to weather, war, or greed, this chamber remains remarkably intact. The patterns have not faded. The symmetry has not surrendered. It’s as though the walls themselves refuse to forget. And in that stubbornness lies something sacred—something that begs us to listen not with ears, but with reverence.

When I first saw this image, I didn’t think of science. I thought of stories.

Who sat here before the photograph? Who entered this chamber seeking answers or healing? Was this a shrine to the dead or a cradle for prophecy? Could the boy in the corner be a descendant of the builders, his blood carrying the very secrets we’ve tried to decipher with books instead of memory?

And what of the woman—still, dignified, present? Did she feel the weight of lineage when she touched the stone? Or was she simply sitting, unaware that centuries later, someone would be writing about her in a language not her own?

This is the paradox of archaeology: we look to ruins for certainty, but all we ever find are better questions.

Mitla’s chamber offers no easy answers. It is not a tomb with gold. It is not a temple with idols. It is a puzzle composed of pattern, space, and silence. And perhaps that’s what makes it powerful. It invites not conquest, but contemplation.

In a world obsessed with answers, Mitla is a rare place that demands you feel before you know.

As you stare at this photo, ask yourself—not what these symbols mean—but what they remember. Ask what kind of culture builds such beauty for the dead. Ask why we, in our modern frenzy, build so little meant to last beyond our own lifetimes. Ask if we’ve truly progressed, or if we’ve just grown louder and more forgetful.

Perhaps, in the end, the chamber is not about death at all.

Perhaps it is about how to survive it. How to thread identity through time, how to encode memory not in fragile parchment, but in stone. Perhaps the Zapotecs knew what we are only now relearning—that legacy is not about empires. It’s about meaning, geometry, silence, and the dignity of those who sit within it.

This image, dusty and still, is alive with lessons.

Will we listen?