In a quiet maternity ward beneath the soft hum of hospital lights, a young mother cradled what history might one day remember as a miracle. Clad in gentle blue scrubs and wearing the kind of smile that only pure awe can craft, she held in her arms not one, not two—but seven perfect newborns, each swaddled in pastel blankets and crowned with tiny lavender caps.

They lay nestled like notes in a lullaby, their chests rising in unison, their faces peaceful and serene. Above them, the words “Gifts from God” fluttered gently in script, echoing the sentiment held deep in the mother’s heart. It was a moment that defied odds, tugged at the fabric of science, and reawakened an ancient truth: that the human story is best told not in stone, but in flesh, heartbeat, and miracle.

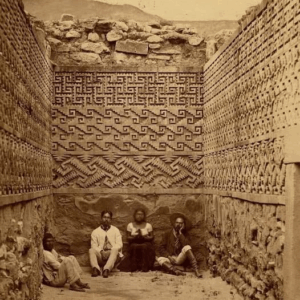

Throughout history, childbirth has been more than a biological event—it has been a sacred ritual, a community celebration, and, at times, a perilous passage. In ancient Mesopotamia, midwives whispered prayers to the goddess Ninhursag, believed to sculpt infants from clay. Egyptian hieroglyphs depict women giving birth in squatting positions, held by birth attendants and shaded by painted lotus flowers, symbols of rebirth.

Archaeological finds in Çatalhöyük, one of the earliest known human settlements in modern-day Turkey, reveal figurines of women with exaggerated curves and wombs. These weren’t idols of lust—they were symbols of fertility and motherhood, elevated to divine status.

Birth, then, was never a private act. It belonged to the community, the cosmos, and the sacred stories that shaped civilizations.

But multiple births? Ah, they were considered omens. Blessings in some cultures. Mysteries in others.

In a 15th-century manuscript buried in the archives of a Benedictine abbey, a monk records the tale of a French farmer’s wife who birthed four children in one labor. The village gathered, not to celebrate, but to pray—for in those days, high-order multiples were seen as either divine favor or the mark of otherworldly intervention.

In ancient Yoruba cosmology, twins—called “Ibeji”—are sacred. To birth more than two? That was to cradle the spirits of ancestors and future kings alike.

And now, in a modern hospital room centuries removed from temple altars and sacred birthing stools, a new chapter is written. She is young, glowing, and perhaps still in disbelief. The weight of seven tiny bodies rests upon her arms, yet her shoulders remain unbowed.

We do not know her name. But we know her legacy.

The moment captured here will ripple forward. Not only through her children—who will grow with stories stitched into the very fabric of their family—but through every viewer who gazes upon this image and feels something stir in their chest. Hope, maybe. Or awe. Or just a deep, quiet breath of gratitude.

We do not need to know the names of her ancestors to see them standing silently behind her. Women who labored in huts, caves, and palaces. Who braved pain without anesthesia. Who died nameless in childbirth, and who sang lullabies into the ears of newborns beneath moonlit skies.

In her arms lies the unbroken chain of motherhood.

Statistically, the birth of septuplets is astoundingly rare. Natural occurrences are nearly nonexistent without fertility treatments, and even then, survival rates often hover on the edge of precarious.

But here they are.

Alive.

Thriving.

Held by the woman who carried them—heart to heartbeat, breath to breath—for what must have been months of both discomfort and wonder. Medical science will rightly take its credit: the ultrasounds, the monitoring, the neonatal care. Yet there is something that medicine cannot measure. Something soft and ancient.

Perhaps that’s why the photo feels almost mythic.

She isn’t just a mother. She is a priestess of life. A vessel of multiplicity. A woman transformed into a living monument, as worthy of reverence as any statue in the Louvre or pyramid in Saqqara.

If archaeologists centuries from now were to unearth this image—carefully preserved in some cloud archive or printed and forgotten in a dusty attic—what would they see?

Not just the clothes or the hospital equipment. Not even the joyful expression. They would see evidence of belief. A cultural reverence for life. An offering.

Anthropologists have always sought patterns in human emotion. They dig through burial sites to interpret grief. They study cave paintings for depictions of joy, fear, and celebration. And if emotional archaeology ever develops tools to measure wonder in digital relics, this photo will shine like obsidian in a field of sand.

Because here is a woman who has touched the impossible and emerged smiling.

The phrase itself—stitched in gentle black across the photo—speaks volumes.

It is not metaphor. It is a worldview.

In many cultures, large families are seen as divine gifts. In rural Nigeria, blessings are counted not in gold, but in the sound of children’s footsteps. In early Ireland, Brehon law offered additional land grants to parents of twins and triplets. In modern America, moments like this trend briefly, then become family legends passed down in bedtime stories and scrapbooks.

But “Gifts from God” is more than a caption. It’s a truth felt deep in the bones.

When you see her smile, you believe it.

What happens next? The photo doesn’t tell us.

Do they grow up laughing in a shared bedroom, forming their own language like many multiples do? Do they scatter to the winds as adults, carrying with them pieces of this beginning? Does the mother sometimes wake and forget, for just a moment, that there are seven?

We do not know.

And maybe we don’t need to.

Because the beauty of a moment like this is that it contains multitudes. Not just the seven she holds, but every story they will write—songs, books, discoveries, whispered secrets between siblings who once floated side by side in a womb too small for so much life.

In the end, this isn’t a story about seven babies.

It’s a story about all of us.

About how humanity continues to unfold, generation after generation. How the smallest things—a heartbeat, a breath, a first cry—can remind us that we are part of something vast and beautiful.

The pyramids were built with stone. Cathedrals with marble. Empires with maps and blood.

But the future?

The future is built in hospital rooms like this. On tired arms and hopeful smiles. On faith, and science, and the sacred act of carrying life into the world.

So when we call them “Gifts from God,” we are not being poetic. We are being precise.

They are not just seven babies.

They are seven chances to start again.